The

Ramayana is the great Indian epic by Valmiki, composed in verse sometime between the first century BCE and the fifth century CE. According to legend, Valmiki's inspiration for the Ramayana was endowed by Brahma, who was pleased by the plaintive lyric that Valmiki composed when a bird was killed by a hunter. Brahma appeared before Valmiki and asked that he write the Ramayana (the

ayana, travels, of Rama) in the same verse form. The

Ramayana was the first Sanskrit poem, and Valmiki's version has remained the most popular both for its historical importance and the style. (

Ramayana on Wikipedia) I read the prose rendition (by Ramesh Menon) of the

Ramayana, mostly in the interest of saving time. I also read the portion of Ralph Griffith's verse translation which was included in the Anderson anthology.

The Ramayana is divided into seven books which follow Rama from birth to death. It is questioned by many whether Valmiki wrote the first and last books, for their style and tone are much different from the other books. They have been deemed crucial to the tale of Rama, however, especially as the first tells of his birth and some of the legends surrounding the characters.

The first book,

Bala Kanda, introduces the legend of Ravana, a king with the power to torment even the gods, for he was granted a boon that no god could harm him. As the gods complain about Ravana, Vishnu (the Supreme Deity) descends and announces that he will be born as Rama, so that he can destroy Ravana in a man's form. Rama is born the son of King Dasaratha, the first of four who were gained by a sacrifice done late in the heirless king's life. Rama is his father's favorite, for he is the strongest, the most devoted to virtue, and the firstborn. Rama is deeply attached to Lakshmana, his youngest brother, who follows him like a shadow. After Rama and Lakshmana destroy the demonic creatures--Rakshasas--who kill and disrupt the ascetics living in the forest, they travel to the city of Vishala, where the king Janaka tells them of Sita, his beautiful adopted daughter. Rama wins Sita as his wife and returns home. All are joyous, but the happiness does not last.

In book two,

Ayodhya Konda, King Dasaratha notices evil omens, and assumes that his death is near, so he arranges for the crowning of Rama as king. However, Dasaratha's youngest and favorite queen, and the mother of his second son (Bharata), becomes jealous of Rama's fortune, wishing the kingdom for her own son. She reminds the king that he had promised her two boons. She then asks that Rama be banished and his brother Bharata be crowned in his place. The king is devastated. He must uphold his promise, even though that means losing Rama. Rama leaves the kingdom the next morning with his wife Sita and his brother Lakshmana, dressed in the rags of an ascetic.

Book three,

Aranya Kanda, details Rama's life after he is banished from the kingdom. He and Lakshmana perform many feats of valor (mostly exterminating Rakshasas), and spend the rest of their time praying, fasting, and waiting for the period of banishment to end. The story turns when Ravana (the powerful Rakshasa king) sees the beautiful Sita. He sends a minion to distract Rama and Lakshmana, then he carries her to his palace across the ocean. When Rama and Lakshmana return to find Sita gone, Rama is heartbroken. He vows to find Sita and wreak vengaence on the Rakshasa king, and here his quest truly begins.

In the fourth book,

Kishkinda Kanda, Rama meets Hanuman, a Vanara (translation: monkey). The Vanaras of the Ramayana are not the monkeys of today, however. Hanuman and his followers are fierce warriors who can grow or shrink in stature, leap incredible distances, and roar as they rush into battle. The Vanaras represent man in a closer relationship with nature. When they fight, they don't use bows or maces or chariots--rather, they use the weapons of the earth: rocks, sticks, tree trunks. Hanuman is the incarnation of Shiva, the destroyer of evil, and he is the son of Vayu, the Hindu deity of the wind. Rama befriends Hanuman by helping him to regain his kingdom, and Hanuman sends his Vanara troops in all directions to find Sita. They eventually learn the the Rakshasa kingdom is across the seemingly endless ocean.

Book five,

Sundara Kanda, begins with Hanuman leaping across the ocean to Lanka, the island of the Rakshasas, hoping against all hope that he won't fall short and plunge to his death into the water below. When Hanuman arrives in Lanka, he shrinks himself and explores the island, trying to become as familiar as possible with the buildings and Rakshasa ways so that that Rama and the Vanaras will be able to defeat Ravana. He finds Sita and tries to rescue her, but she insists that she must wait for Rama. Before Hanuman leaves, he witnesses Ravana trying unsuccessfully to woo Sita. Ravana declares that if Sita does not give into him within two months, he will have his guards cut her to pieces. Angered by Ravana's claim Hanuman destoys the mango grove they are in and sets fire to the city before leaping back across the ocean and conferring with Rama.

In the sixth book,

Yuddha Kanda, Rama decides that a bridge must be built across the ocean so that he, Lakshmana, and the entire Vanara army can get to Lanka. As they begin building, Ravanas brother arrives. He has deserted the ignoble Ravana and wants to aid Rama in the ensuing battle. Rama and his army reach Lanka and a fierce battle threatens to destroy both armies until it is decided that the victor should be decided by combat between Rama and Ravana. The opponents seem evenly matched, but Rama defeats Ravana, and

a shower of petals falls. Sita and Rama are reunited, but Rama states that "no man of honor can take home a woman who has lived in his enemy's house for so many moons." Sita must prove her virtue by walking into fire. After she does so, and survives, Rama accepts her as his wife.

The seventh book,

Uttara Kanda, tells the stories of Rama and Sita after they return to Rama's kingdom. Rama learns that the people of his kingdom suspect that Sita has betrayed him, and that they fear their wives will follow what they believe to be Sita's example. Sita is considered to be unfit as Rama's queen, and she is banished. She is abandoned, and becomes an ascetic. She gives birth to twin boys months later, and those twins eventually lead Rama to her. Rama realizes he shouldn't have banished Sita and asks her to return as his queen. Sita admits that she will always love Rama, but that she no longer wishes to live in this world, and she is escorted by the Earth Goddess into the earth. Rama grieves the loss of Sita, and the rest of his ten thousand year rule is lonely, though fruitful for his people. Late in life Rama is approached by a messenger who informs him that he is the incarnation of Vishnu. The messenger is Yama (Death), and he was sent by Brahma to give Rama the option of leaving the earth. Rama realizes that his work on earth is complete and leaves his corporeal form.

The theme of karma, a summation and assessment of all one's action, is central to the poem, and all characters experience life (and, more importantly, death) according to their ability to fulfill their respective duties on earth. Ravana's character is very interesting: although he was a good and just king to his people, and though he was pious and performed many rituals to the gods, his actions were motivated by a lust for power. For actions to be beneficial to karma, they must be selflessly performed as a duty to God, without thought to the reward or punishment. Ravana merely sought to please the gods so that they would bestow their powers on him. His concern for the self led to a proud nature, and to the destruction of every material and worldly connection that Ravana strove to preserve in his fight against Rama.

Sita's role in the epic is also very intriguing. Being herself an incarnation of the powerful god Lakshmi (and Vishnu), she is in full possession of powers capable of destroying Ravana if she tried. But she doesn't try. There are no moments during which Sita is tempted to take matters into her own hands and solve the problem of her own captivity. She waits patiently for Rama to arrive and save her. This complacency seemed very strange at first--it would seem that Sita's most virtuous act would be to vanquish her oppressor. But Sita's role as a woman forbids her from taking action, powerful though she may be. I believe, however, that it is Sita's refusal to engage in violence which allows Rama's victory. Sita remains in ascetic prayer during her captivity, ever invoking the gods, pleading for their aid and interference. Her prayers are heard even more clearly because she is pure of evil intent--she does not wish to harm Ravana out of spite, only out of justice. Using power is not the dharma of a woman, and if Sita were to ignore her dharma, she would become tainted. Sita knows her role, and fulfills it by patiently accepting the situation. Her role symbolizes the unattachment to the earthly condition that man must realize in order to lose pride and find God.

The last book of the

Ramayana is a testament to this release of material attachment. Rama must banish the queen whom he loves dearly--he must fulfill his duty as king without attachment as an act of love for God. He fears that allowing Sita to continue as his queen would cause a disintegration in the social organization of his kingdom which only the sanctity of marriage holds in place. Rama must choose then between the love for his queen, and ultimately, the love for God. He chooses God and dharma, and suffers alone while on earth. But he finds God (in himself) before his death, and his soul ascends to heaven.

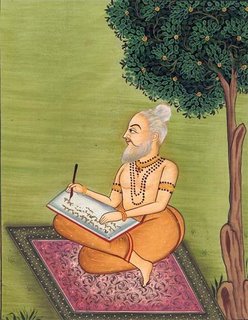

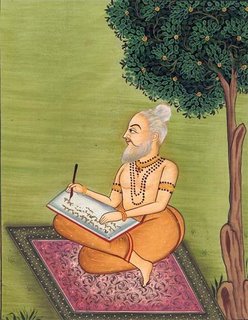

The image at the top right is of Valmiki composing the

Ramayana, and can found

here. The next image is of Dasaratha, grieving as he banishes Rama (

source). Following is Hanuman and Rama (

source). And lastly, Rama, flanked by Lakshmana and Sita, with Hanuman kneeling in front (

source).